Usage

Formatting

sciform provides two primary methods for formatting numbers into

scientific formatted strings.

The first is via the Formatter object and the second is

using string formatting and the

Format Specification Mini-Language (FSML) with the

SciNum object.

Formatter

The Formatter object is initialized and configured using a

number of formatting options described in Formatting Options.

The Formatter object is then called with a number and returns

a corresponding formatted string.

>>> from sciform import Formatter

>>> formatter = Formatter(

... round_mode="dec_place", ndigits=6, upper_separator=" ", lower_separator=" "

... )

>>> print(formatter(51413.14159265359))

51 413.141 593

>>> formatter = Formatter(round_mode="sig_fig", ndigits=4, exp_mode="engineering")

>>> print(formatter(123456.78))

123.5e+03

It is not necessary to provide input for all options. At format time, any un-populated options will be populated with the corresponding options from the global options. See Global Options for details about how to view and modify the global options.

SciNum

The sciform FSML can be accessed via the

SciNum object.

Python numbers specified as string, int,

float, or Decimal objects are cast to SciNum

objects which can be formatted using the sciform

FSML.

>>> from sciform import SciNum

>>> num = SciNum(123456)

>>> print(f"{num:!2f}")

120000

Value/Uncertainty Formatting

One of the most important use cases for scientific formatting is

formatting a value together with its specified uncertainty, e.g.

84.3 ± 0.2.

sciform provides the ability to format pairs of numbers into

value/uncertainty strings.

sciform attempts to follow

BIPM

or NIST

recommendations for conventions when possible.

Value/uncertainty pairs can be formatted either by passing two numbers

into a Formatter, configured with the corresponding

Formatting Options and Value/Uncertainty Formatting Options, or by

using the SciNum object.

>>> val = 84.3

>>> unc = 0.2

>>> formatter = Formatter(ndigits=2)

>>> print(formatter(val, unc))

84.30 ± 0.20

>>> from sciform import SciNum

>>> num = SciNum(val, unc)

>>> print(f"{num:!2}")

84.30 ± 0.20

Value/uncertainty pairs can also be formatted using a parentheses notation in which the uncertainty is displayed in parentheses following the value. See BIPM Guide Section 7.2.2.

>>> print(f"{num:!2()}")

84.30(20)

Value/uncertainty pairs are formatted according to the following algorithm:

Rounding is always performed using significant figure rounding applied to the uncertainty. See Rounding for more details about possible rounding options.

The value is rounded to the decimal place corresponding to the least significant digit of the rounded uncertainty.

The value for the exponent is resolved by using

exp_modeandexp_valwith the larger of the value or uncertainty.The value and uncertainty mantissas are determined according to the value of the exponent determined in the previous step.

The value and uncertainty mantissas are formatted together with the exponent according to other user-selected display options.

Formatted Input

Both the Formatter format function and SciNum

constructor accept str, int, float, and

Decimal input for the value and optionally accept the same

types for the uncertainty.

>>> from decimal import Decimal

>>> from sciform import Formatter

>>>

>>> formatter = Formatter(ndigits=4)

>>> print(formatter("32", "9"))

32.000 ± 9.000

>>> print(formatter(32, 9))

32.000 ± 9.000

>>> print(formatter(32.00, 9.00))

32.000 ± 9.000

>>> print(formatter(Decimal("32.000"), Decimal("9.000")))

32.000 ± 9.000

These example strings can be natively cast to numeric types like

int, float, or Decimal.

However, Formatter and SciNum also accept

formatted strings which contain the numeric information, but with more

sophisticated formatting.

>>> print(formatter("+ 123_456,789 987 n"))

0.0001235

Here the string "+ 123_45,789 987 n" is re-interpreted by the

Formatter as the number 12345.789987e-09.

The e-09 arises as the reverse translation of the SI “nano” prefix

n.

When this is formatted in fixed point mode with 4 significant digits the

result is "0.0001235".

Instead of passing in two inputs, one representing the value and one representing the uncertainty, it is possible to pass in one input which contains information about both the value and the uncertainty.

>>> print(formatter("(123.0 ± 0.4) m"))

0.1230000 ± 0.0004000

>>> print(formatter("(123 +/- 0.4) m"))

0.1230000 ± 0.0004000

Note that the first example input string is an example sciform

output string that would have resulted from various options and inputs

while the second example input string is not an example sciform

output string.

Any sciform output string can also be used as an input string.

However, some input strings can be supplied which are not valid

sciform outputs.

For inputs, it is not necessary that the value and uncertainty are expressed to the same lowest decimal place. By contrast,

sciformoutputs will always format the value and uncertainty to the same lowest decimal place.For inputs, the ASCII

+/-symbols may be used to separate the value from the uncertainty. By contrast,sciformwill always use the Unicode±symbol for direct outputs (noting that the±symbol can be converted into+/-afterwards usingFormattedNumber.as_ascii(), see Output Conversion).

Note that the formatting of the input strings has no bearing on the formatting of the resulting outputs.

Like sciform outputs, the input value/uncertainty pairs must

always share the exponent string.

>>> print(formatter("(1.2 +/- 0.1)e+03"))

1200.0 ± 100.0

>>> print(formatter("1.2e+03 +/- 0.1e+03"))

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

ValueError: Input string "1.2e+03 +/- 0.1e+03" does not match any expected input format.

Inputs can use parentheses uncertainty notation and will be interpreted using the following rules.

The value string will always be directly converted to a float.

If the uncertainty string contains a decimal symbol then it will be directly converted to a float.

If the value string contains a decimal symbol but the uncertainty string does not then the string is parsed according to trimmed parentheses notation. In this case the uncertainty is left padded with a leading

"0."and then a sufficient number of zeros so that the least significant digit of the uncertainty matches the least significant digit of the value.

If the uncertainty contains more digits than appear in the fractional part of the value then this padding is impossible and it is not clear what the value of the uncertainty is. In this case an exception is raised.

>>> print(formatter("1(100)"))

1.0 ± 100.0

>>> print(formatter("123.4(5.42)"))

123.400 ± 5.420

>>> print(formatter("123.4(5)"))

123.4000 ± 0.5000

>>> print(formatter("123.4(56)"))

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

ValueError: Invalid value/uncertainty pair for parentheses uncertainty: "123.4(56)". If a decimal symbol appears in the value but not in the uncertainty then the number of the digits in the uncertainty may not exceed the number of digits in the fractional part of the value.

If the input string contains information about the uncertainty then a second argument, which would otherwise specify the uncertainty, is not allowed

>>> print(formatter("123(4)", 4))

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

ValueError: Value input string "123(4)" already includes an uncertainty, (4). It is not possible to also pass in an uncertainty (4) directly.

As demonstrated above, the input string parser can parse translated

exponents such as "n" -> "e-09".

These translations are performed by first checking the default SI

prefixes along with any global extra_si_prefixes, then checking

the default parts-per forms along with any global

extra_parts_per_forms, then checking the default IEC prefixes along

with any global extra_iec_prefixes.

If an IEC prefix is detected then the exponent base is chosen to be 2.

if no valid translations are discovered or more than one valid

translation is discovered an exception is raised.

>>> from sciform import GlobalOptionsContext

>>> formatter = Formatter()

>>> with GlobalOptionsContext(add_c_prefix=True):

... print(formatter("32 c"))

0.32

>>> print(formatter("32 c"))

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

ValueError: Unrecognized prefix: "c". Unable to parse input.

>>> with GlobalOptionsContext(extra_si_prefixes={-12: "ppb"}):

... print(formatter("42 ppb"))

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

ValueError: Multiple translations found for "ppb": [-12, -9]. Unable to parse input.

In the final example, the SI translation for an exponent of -12 was

re-mapped to "ppb" according to the “long scale” definition of

billion.

This collides with the “short scale” definition of billion that maps

-9 to "ppb" as a default parts per form.

This issue could be corrected as follows.

>>> with GlobalOptionsContext(

... exp_mode="engineering",

... extra_parts_per_forms={-9: None, -12: "ppb"}

... ):

... print(formatter("42 ppb"))

42e-12

In most cases the parser can determine whether the decimal symbol is

"." or ",".

If both

"."and","appear in a formatted value then whichever comes earlier must be the upper separator and whichever comes later must be the lower separator. E.g.123.456,789must have","as the decimal separator.If one separator appears more than once it must be the upper separator. E.g.

123,456,789must have"."as the decimal separator.If one separator appears once but it is preceded by more than 3 digits, or it is followed by any number of digits other than 3, then that separator must be the decimal separator. E.g. in both

1234.567and12.3we must have that"."is the decimal separator.In some cases the decimal separator cannot be determined, e.g.

123456,123,456,12.345.

sciform first tries to infer the decimal separator from the

both the value and the uncertainty.

If these inferences are successful and disagree then an exception is

raised.

If the inferences agree or only one succeeds then the succeeding result

is selected as the decimal separator.

If neither inference is successful then the decimal separator is

selected either from the populated options on the local

Formatter or from the global options.

>>> formatter = Formatter(decimal_separator=".")

>>> print(formatter("1234,567"))

1234.567

>>> print(formatter("123,45"))

123.45

>>> print(formatter("123,45 +/- 345.578"))

123 ± 345578

>>> print(formatter("12.45 +/- 2,34"))

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

ValueError: Value "12.45" and uncertainty "2,34" have different decimal separators.

>>> formatter = Formatter(decimal_separator=",")

>>> print(formatter("123,456"))

123,456

>>> formatter = Formatter()

>>> with GlobalOptionsContext(decimal_separator=","):

... print(formatter("123,456"))

123,456

The same parsing rules apply to SciNum construction

>>> print(f'{SciNum("+ 123_456,789 987 n"):!4f}')

0.0001235

>>> print(f'{SciNum("(123.0 ± 0.4) m"):!4f}')

0.1230000 ± 0.0004000

>>> print(f'{SciNum("(123 +/- 0.4) m"):!4f}')

0.1230000 ± 0.0004000

>>> print(f'{SciNum("123(4)")}')

123 ± 4

Output Conversion

Typically the output of the Formatter is used as a regular

python string.

However, the Formatter returns a FormattedNumber

instance.

The FormattedNumber class

subclasses str and in many cases is used like a normal python

string.

However, the FormattedNumber class

exposes methods to convert the standard string representation into

LaTeX, HTML, or ASCII representations.

The LaTeX and HTML representations may be useful when sciform

outputs are being used in contexts outside of e.g. text terminals such

as Matplotlib plots,

Jupyter notebooks, or

Quarto documents which support richer display

functionality than Unicode text.

The ASCII representation may be useful if sciform outputs are

being used in contexts in which only ASCII, and not Unicode, text is

supported or preferred.

These conversions can be accessed via the

FormattedNumber.as_latex(),

FormattedNumber.as_html(), and

FormattedNumber.as_ascii() methods on the

FormattedNumber class.

>>> formatter = Formatter(

... exp_mode="scientific",

... exp_val=-1,

... upper_separator="_",

... superscript=True,

... )

>>> formatted = formatter(12345)

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_latex()}")

123_450×10⁻¹ -> $123\_450\times10^{-1}$

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_html()}")

123_450×10⁻¹ -> 123_450×10<sup>-1</sup>

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_ascii()}")

123_450×10⁻¹ -> 123_450e-01

>>> formatter = Formatter(

... exp_mode="percent",

... lower_separator="_",

... )

>>> formatted = formatter(0.12345678, 0.00000255)

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_latex()}")

(12.345_678 ± 0.000_255)% -> $(12.345\_678\:\pm\:0.000\_255)\%$

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_html()}")

(12.345_678 ± 0.000_255)% -> (12.345_678 ± 0.000_255)%

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_ascii()}")

(12.345_678 ± 0.000_255)% -> (12.345_678 +/- 0.000_255)%

>>> formatter = Formatter(exp_mode="engineering", exp_format="prefix", ndigits=4)

>>> formatted = formatter(314.159e-6, 2.71828e-6)

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_latex()}")

(314.159 ± 2.718) μ -> $(314.159\:\pm\:2.718)\:\text{\textmu}$

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_html()}")

(314.159 ± 2.718) μ -> (314.159 ± 2.718) μ

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_ascii()}")

(314.159 ± 2.718) μ -> (314.159 +/- 2.718) u

The LaTeX enclosing "$" math environment symbols can be optionally

stripped:

>>> formatter = Formatter(exp_mode="engineering", exp_format="prefix", ndigits=4)

>>> formatted = formatter(314.159e-6, 2.71828e-6)

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_latex(strip_math_mode=False)}")

(314.159 ± 2.718) μ -> $(314.159\:\pm\:2.718)\:\text{\textmu}$

>>> print(f"{formatted} -> {formatted.as_latex(strip_math_mode=True)}")

(314.159 ± 2.718) μ -> (314.159\:\pm\:2.718)\:\text{\textmu}

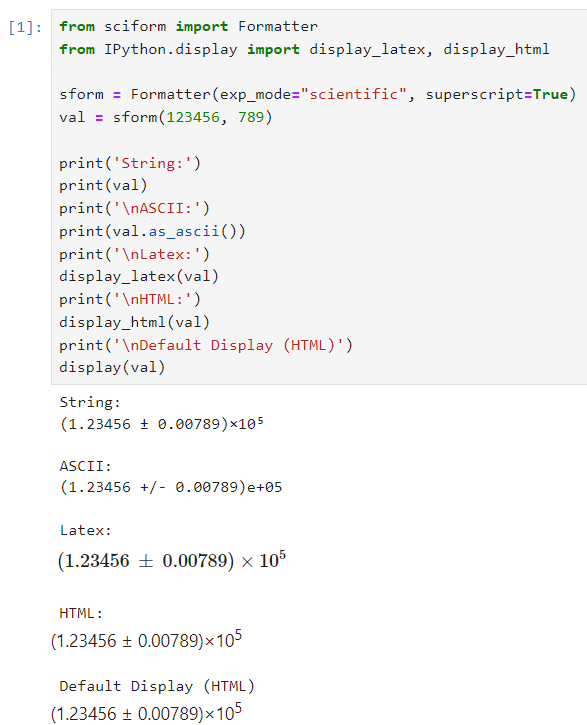

In addition to exposing

FormattedNumber.as_latex() and

FormattedNumber.as_html(),

the FormattedNumber class defines

the aliases

FormattedNumber._repr_latex_() and

FormattedNumber._repr_html_().

The

IPython display functions

looks for these methods, and, if available, will use them to display

prettier representations of the class than the Unicode __repr__

representation.

Here is example FormattedNumber usage in a Jupyter notebook.

Global Options

It is possible to modify the global options for sciform to avoid

repetition of verbose configuration options or format specification

strings.

When the user creates a Formatter object or formats a string

using the FSML, they typically do not specify settings for

all available options.

In these cases, the unpopulated options resolve their values from the

global options at format time.

The sciform default global options can be viewed using

get_default_global_options()

>>> from sciform import get_default_global_options

>>> print(get_default_global_options())

PopulatedOptions(

'exp_mode': 'fixed_point',

'exp_val': AutoExpVal,

'round_mode': 'sig_fig',

'ndigits': AutoDigits,

'upper_separator': '',

'decimal_separator': '.',

'lower_separator': '',

'sign_mode': '-',

'left_pad_char': ' ',

'left_pad_dec_place': 0,

'exp_format': 'standard',

'extra_si_prefixes': {},

'extra_iec_prefixes': {},

'extra_parts_per_forms': {},

'capitalize': False,

'superscript': False,

'nan_inf_exp': False,

'paren_uncertainty': False,

'pdg_sig_figs': False,

'left_pad_matching': False,

'paren_uncertainty_trim': True,

'pm_whitespace': True,

)

The global options can be modified using the set_global_options()

function.

Any options passed will overwrite the corresponding options in the

current global options and any unfilled options will remain unchanged.

The current global options can be viewed using

get_global_options().

The global options can be reset to the sciform default global

options using reset_global_options().

>>> from sciform import set_global_options, get_global_options, reset_global_options

>>> set_global_options(

... left_pad_char="0",

... exp_mode="engineering_shifted",

... ndigits=4,

... decimal_separator=",",

... )

>>> print(get_global_options())

PopulatedOptions(

'exp_mode': 'engineering_shifted',

'exp_val': AutoExpVal,

'round_mode': 'sig_fig',

'ndigits': 4,

'upper_separator': '',

'decimal_separator': ',',

'lower_separator': '',

'sign_mode': '-',

'left_pad_char': '0',

'left_pad_dec_place': 0,

'exp_format': 'standard',

'extra_si_prefixes': {},

'extra_iec_prefixes': {},

'extra_parts_per_forms': {},

'capitalize': False,

'superscript': False,

'nan_inf_exp': False,

'paren_uncertainty': False,

'pdg_sig_figs': False,

'left_pad_matching': False,

'paren_uncertainty_trim': True,

'pm_whitespace': True,

)

>>> reset_global_options()

The global options can be temporarily modified using the

GlobalOptionsContext context manager.

The context manager is configured using the same options as

Formatter and set_global_options().

Within the context of GlobalOptionsContext manager, the

global options take on the specified input settings, but when the

context is exited, the global options revert to their previous values.

>>> from sciform import GlobalOptionsContext, SciNum

>>> num = SciNum(0.0123)

>>> print(f"{num:.2ep}")

1.23e-02

>>> with GlobalOptionsContext(add_c_prefix=True):

... print(f"{num:.2ep}")

1.23 c

>>> print(f"{num:.2ep}")

1.23e-02

Note that the FSML does not provide complete control over

all possible format options.

For example, there is no code in the FSML for configuring

the pdg_sig_figs option.

If the user wishes to configure these options, but also use the

FSML, then they must do so by modifying the global

options.

Formatter Options

The Formatter options are configured by constructing a

Formatter and passing in keyword arguments corresponding to the

desired options.

Only a subset of available options need be specified.

The user input during Formatter construction can be viewed

using the Formatter.input_options property.

>>> formatter = Formatter(

... exp_mode="engineering",

... round_mode="sig_fig",

... ndigits=2,

... superscript=True,

... )

>>> print(formatter.input_options)

InputOptions(

'exp_mode': 'engineering',

'round_mode': 'sig_fig',

'ndigits': 2,

'superscript': True,

)

The Formatter.input_options property is a InputOptions

instance.

The string representation of this object indicates the explicitly

populated options.

A dictionary of these populated options is available via the

InputOptions.as_dict() method.

>>> print(formatter.input_options.as_dict())

{'exp_mode': 'engineering', 'round_mode': 'sig_fig', 'ndigits': 2, 'superscript': True}

Both populated and unpopulated options can be accessed by direct attribute access.

>>> print(formatter.input_options.round_mode)

sig_fig

>>> print(formatter.input_options.exp_format)

None

In addition to viewing the user input options, it is possible to preview

the result of populating the unpopulated options with the corresponding

global options by using the Formatter.populated_options

property.

>>> print(formatter.populated_options)

PopulatedOptions(

'exp_mode': 'engineering',

'exp_val': AutoExpVal,

'round_mode': 'sig_fig',

'ndigits': 2,

'upper_separator': '',

'decimal_separator': '.',

'lower_separator': '',

'sign_mode': '-',

'left_pad_char': ' ',

'left_pad_dec_place': 0,

'exp_format': 'standard',

'extra_si_prefixes': {},

'extra_iec_prefixes': {},

'extra_parts_per_forms': {},

'capitalize': False,

'superscript': True,

'nan_inf_exp': False,

'paren_uncertainty': False,

'pdg_sig_figs': False,

'left_pad_matching': False,

'paren_uncertainty_trim': True,

'pm_whitespace': True,

)

The Formatter.populated_options property is a

PopulatedOptions instance.

It is recalculated each time the property is accessed so that the output

always reflects the current global options.

Like the InputOptions class, the PopulatedOptions

class provides access to its options via direct attribute access and via

a PopulatedOptions.as_dict() method.

The FormattedNumber class stores a record of the

PopulatedOptions that were used to generate it.

>>> formatter = Formatter(

... exp_mode="engineering",

... round_mode="sig_fig",

... ndigits=2,

... superscript=True,

... )

>>> formatted = formatter(12345.678, 3.4)

>>> print(formatted)

(12.3457 ± 0.0034)×10³

>>> print(formatted.populated_options)

PopulatedOptions(

'exp_mode': 'engineering',

'exp_val': AutoExpVal,

'round_mode': 'sig_fig',

'ndigits': 2,

'upper_separator': '',

'decimal_separator': '.',

'lower_separator': '',

'sign_mode': '-',

'left_pad_char': ' ',

'left_pad_dec_place': 0,

'exp_format': 'standard',

'extra_si_prefixes': {},

'extra_iec_prefixes': {},

'extra_parts_per_forms': {},

'capitalize': False,

'superscript': True,

'nan_inf_exp': False,

'paren_uncertainty': False,

'pdg_sig_figs': False,

'left_pad_matching': False,

'paren_uncertainty_trim': True,

'pm_whitespace': True,

)

Formatter Options Edge Cases

In most cases, at format/option population time, any non-None options

in the InputOptions will be exactly copied over to the

PopulatedOptions and any None options will be exactly copied

over from the global options at format time.

However, a few options have slightly more complicated behavior.

>>> from sciform import set_global_options, get_global_options, reset_global_options

>>> set_global_options(extra_si_prefixes={-2: "cm"})

>>> print(get_global_options().extra_si_prefixes)

{-2: 'cm'}

>>> formatter = Formatter(add_c_prefix=True)

>>> print(formatter.input_options.extra_si_prefixes)

None

>>> print(formatter.populated_options.extra_si_prefixes)

{-2: 'c'}

>>> reset_global_options()

Somewhat surprisingly, even though extra_si_prefixes is unpopulated

in the Formatter, it does not get populated with the

corresponding global options extra_si_prefixes.

This is because the Formatter has add_c_prefix=True.

If extra_si_prefixes=None but add_c_prefix=True then the same

population behavior as if extra_si_prefixes={-2: 'c'} is realized.

If extra_si_prefixes is a dictionary then {-2: 'c'} is added to

the dictionary if -2 is not already a key in the dictionary.

If -2 already appears in the dictionary then its value is not

overwritten.

>>> set_global_options(extra_si_prefixes={-2: "cm"})

>>> print(get_global_options().extra_si_prefixes)

{-2: 'cm'}

>>> formatter = Formatter(extra_si_prefixes={-15: 'fermi'}, add_c_prefix=True)

>>> print(formatter.input_options.extra_si_prefixes)

{-15: 'fermi'}

>>> print(formatter.populated_options.extra_si_prefixes)

{-15: 'fermi', -2: 'c'}

>>> reset_global_options()

>>> formatter = Formatter(extra_si_prefixes={-2: 'cm'}, add_c_prefix=True)

>>> print(formatter.input_options.extra_si_prefixes)

{-2: 'cm'}

>>> print(formatter.populated_options.extra_si_prefixes)

{-2: 'cm'}

>>> reset_global_options()

Analogous behavior occurs for the add_small_si_prefixes and

add_ppth_form Formatter options.

Note also that these three options, add_c_prefix,

add_small_si_prefixes, and add_ppth_form appear in the

InputOptions instance if they have been explicitly set, but

they never appear in the PopulatedOptions instance.

Rather, only the populated extra_si_prefixes or

extra_parts_per_forms are appropriately populated.

Finally, if integer 0 is passed into left_pad_char then

integer 0 will be stored in the InputOptions, but it will

be converted to string "0" in the PopulatedOptions.

>>> formatter = Formatter(left_pad_char=0)

>>> print(type(formatter.input_options.left_pad_char))

<class 'int'>

>>> print(type(formatter.populated_options.left_pad_char))

<class 'str'>

Note on Decimals and Floats

Numerical data can be stored in Python

float

or

Decimal objects.

float instances represent numbers using binary which means

they are often only approximations of the decimal numbers users have in

mind when they use float.

By contrast, Decimal objects store sequences of integers

representing the decimal digits of the represented numbers so,

Decimal instances are, therefore, exact representations of

decimal numbers.

Both of these representations have finite precision which can cause

unexpected issues when manipulating numerical data.

However, in the Decimal class, the main issue is that

numbers may be truncated if their precision exceeds the configured

Decimal precision, but the rounding will be as expected.

That said, the precision used for Decimal numbers can

easily be modified if necessary.

float instances, unfortunately, may exhibit more surprising

behavior, as will be explained below.

For these reasons, the sciform module uses Decimal

representations in its internal formatting algorithms.

Note, however, that Decimal arithmetic operations are less

performant that float operations.

So, unless very high precision is needed at all steps of the

calculation, the suggested workflow is to store and manipulate numerical

data as float instances, and only convert to Decimal,

or format using sciform, as the final step when numbers are being

displayed for human readers.

Float Issues

Here we would like to highlight some important facts and possible issues

with float objects that users should be aware of if they are

concerned with the exact decimal representation of their numerical data.

Python uses double-precision floating-point format for its

float. In this format, afloatoccupies 64 bits of memory: 52 bits for the mantissa, 11 bits for the exponent and 1 bit for the sign.Any decimal with 15 digits between about

± 1.8e+308can be uniquely represented by afloat. However, two decimals with more than 15 digits may map to the samefloat. For example,float(8.000000000000001) == float(8.000000000000002)returnsTrue. See “Decimal Precision of Binary Floating Point Numbers” for more details.If any

floatis converted to a decimal with at least 17 digits then it will be converted back to the samefloat. See “The Shortest Decimal String that Round-Trips: Examples” for more details. However, manyfloatinstances can be “round-tripped” with far fewer digits. The__repr__()for the pythonfloatclass converts thefloatto a string decimal representation with the minimum number of digits such that it round trips to the samefloat. For example we can see the exact decimal representation of thefloatwhich0.1is mapped to:print(Decimal(float(0.1)))gives"0.1000000000000000055511151231257827021181583404541015625". Howeverprint(float(0.1))just gives"0.1". That is,0.1000000000000000055511151231257827021181583404541015625and0.1map to the samefloatbut thefloat__repr__()algorithm presents us with the shorter (more readable) decimal representation.

The python documentation

goes into some detail about possible issues one might encounter when

working with float instances.

Here we would like to highlight two specific issues.

Rounding. Python’s round() function uses a “round-to-even” or “banker’s rounding” strategy in which ties are rounded so the least significant digit after rounding is always even. This ensures data sets with uniformly distributed digits are not biased by rounding. Rounding of

floatinstances may have surprising results. Consider the decimal numbers0.0355and0.00355. If we round these to two significant figures using a “round-to-even” strategy, we expect the results0.036and0.0036respectively. However, if we try to perform this rounding forfloatwe get an unexpected result. We see thatround(0.00355, 4)gives0.0036as expected butround(0.0355, 3)gives0.035. We can see the issue by looking at the decimal representations of the correspondingfloatinstances.print(Decimal(0.0355))gives"0.035499999999999996835864379818303859792649745941162109375"which indeed should round down to0.035whileprint(Decimal(0.00355))gives"0.003550000000000000204003480774872514302842319011688232421875"which should round to0.0036. So, we see that the rounding behavior forfloatmay depend on digits of the decimal representation of thefloatwhich are beyond the minimum number of digits necessary for thefloatto round trip and, thus, beyond the number of digits that will be displayed by default.Representation of numbers with high precision. Conservatively,

floatprovides 15 digits of precision. That is, any two decimal numbers (within thefloatrange) with 15 or fewer digits of precision are guaranteed to correspond to uniquefloatinstances. Decimal numbers with 16 digits or more of precision may not correspond to uniquefloatinstances. It is rare, in scientific applications, that we require more than 15 digits of precision, but in some cases we do. One example is precision frequency metrology, such as that involved in atomic clocks. The relative uncertainty of primary frequency standards is approaching one part in 10-16. This means that measured quantities may require up to 16 digits to display. Indeed, consider Metrologia 55 (2018) 188–200. In Table 2 the 87 Rb ground-state hyperfine splitting is cited as6 834 682 610.904 312 6 Hzwith 17 digits. Suppose the last digit was a5instead of a6. Pythonfloatcannot tell the difference:float(6834682610.9043126) == float(6834682610.9043125)returnsTrue.

How sciform Handles Decimals and Floats

To support predictable rounding and the representation of high precision

numbers, sciform casts the numbers it is presenting to

Decimal objects during its formatting algorithm.

Numbers are input into sciform either as the input to a

Formatter or when instantiating a SciNum object.

In all cases the input will typically be a Decimal,

float, str, or int.

Decimal, str and int are unambiguously

converted to Decimal objects.

For float inputs, the values are first cast to str

instances to get their shortest round-trippable decimal representations.

These shortest round-trippable strings are then converted into

Decimal instances.

For high precision applications it is recommended that users provide

input to sciform either as str or Decimal.